Owen Barfield: an introduction

His big idea

Barfield argued for his big idea in two ways:

Owen Barfield in short films

What he said about everything from consciousness to C.S. Lewis explained in a series of minute-long films.

Owen Barfield & David Bohm

A report on a discussion with the great physicist that only recently came to light.

Evolving Consciousness conference

Reports and films of stellar speakers from this gathering.

A Secret History of Christianity

Lots about my book including extracts and endorsements.

Life and thought

What does this mean about the evolution of human consciousness?

It implies that the origins of language are not rooted in grunt and sign references to objects – perhaps a banana to eat or a leopard to avoid – that were then loaded up with extra meanings by fanciful human brains. Instead, words were from the get-go loaded with the inner and outer meanings that our ancestors detected in the world around them, and consciously articulated when they first started to speak.

Language is a phenomenon that arose when hominids engaged with life not just to survive but to share in the great rush of it that they felt teeming around them. It sprang from an involvement with things. ‘The first metaphors were not artificial but natural,’ summarised Barfield.

They are the tokens of a prehistoric communion. They are the record of an increasingly conscious awareness of links with the inner life of the cosmos. That participation split apart when our very much more recent ancestors, on the cusp of a modern, scientific consciousness, stopped experiencing the world in the enchanted, natural way.

You could say that it would be better to assume what language itself implies. It is so powerfully meaningful because it is innately meaningful. Its poetry enables us to perceive deeper structures of reality that our empirical senses alone couldn’t detect. Words channel that vitality. They have soul because nature does – for all that, these days, we struggle to feel it and are quite inclined to disbelieve it.

It is, in part, a recognition of this loss that has led the English writer Robert Macfarlane on a project to rescue words. As he explains in Landmarks: ‘[What] is lost along with this literacy is something precious: a kind of word magic, the power that certain terms possess to enchant our relations with nature and place.’

The point is that words that have come to describe the inner life of human beings can have evolved only if the cosmos is full of spirit. The first humans were not inventive, but often deluded, onlookers. They were intelligent participants in that wider consciousness. Their difference from other creatures lay only in a capacity consciously to communicate the meaning they felt pulsing around them.

In History, Guilt and Habit (1979), Barfield concluded that the evolution of words ‘always points us back to a cultural period when there was a much closer interpenetration between thinking and perceiving than is the case with us today’.

Or as Alexander von Humboldt, one of the key figures at the origins of modern science, realised: ‘Nature everywhere speaks to man in a voice familiar to his soul.’ And moreover, Humboldt concluded, this is the reason science can be done.

(Some of this section comes from a longer essay I wrote on the evolution of language published by Aeon, which is online here.”

Why did C.S. Lewis call Barfield his “anti-self”?

In Surprised by Joy, Lewis calls Barfield his “anti-self”. Barfield was to dedicate one of his key books to Lewis with William Blake’s adage: “Opposition is true friendship.” Soon after they met, they launched into a series of embattled discussions that they came to call their “Great War”.

It was the time during which Barfield laid down intellectual foundations to underpin his spiritual awakening, about which Lewis was profoundly skeptical. The future Christian apologist was far from any belief in theism at the time, and it seemed to him that Barfield was deluded.

So, where Barfield argued that the imagination was as important as reason for discerning and relating to the nature of things, Lewis prioritized reason and trusted cooler conceptual knowledge alone. Where Barfield noticed qualities of being echoing in his soul as he read poetry and myths, Lewis held that poetry and myth were meaningful insofar as they express human ideas only.

Barfield caught the difference in a letter to Lewis: “to me [truth] is not a sort of accurate copy or reflection of something, but it is reality itself taking the form of human consciousness.” You can awaken to the pulse that sustains existence and know it. Lewis remained doubtful.

What’s it got to do with the Hebrews, Greeks and Jesus?

That’s the subject of my book. In short, ancient Hebrews and Greeks underwent the shift in consciousness Barfield describes, and that prepared the way for Jesus.

Amongst the ancient Hebrews, the change began in the momentous century that featured the northern and southern kingdoms exiles in Babylon and ended with the return to Jerusalem. It was the age in which the Bible was first written down, and the prophets first formulated a clear doctrine of monotheism. The withdrawal of participation was manifested most directly in the ban on idols. The beginnings of a new way of participating in nature and the cosmos began with reflections upon the nameless name originally given to Moses: Yahweh’s tremendous “I AM”.

Amongst the ancient Greeks, the epochal shift began a few decades later, in the fifth century BCE. It was the age in which figurative sculptures seemed to wake up; human personhood and individuality became a fascination for playwrights; and a novel sense of the cosmos gripped the first philosophers, who also wrestled with the crisis of meaning that ensued. The withdrawal of participation was felt in the experience of having a conscience and of quarrelling with gods. The beginnings of a new way of re-participating began with reflections on how to care for the soul, and thereby cultivate a self-conscious relationship with what is good, beautiful and true.

It’s at this point that we get to the significance of Barfield’s discoveries for Christianity.

According to him, the evolution of consciousness did not settle into a fully flourishing reciprocal consciousness in the Hellenistic world, for all the genius of the ancient Greeks and Jews. That took a further event, which had in fact begun to be expected by some of them.

The full implications of the subtle shifts that, by then, were unfolding inexorably had to be incarnated. To be wholly realised, the inside of the cosmos needed to be manifested, not in the ideas of powerful teachers but in the life of an individual. Only then, could the process of disentangling the inner life of human beings from the inner life of nature turn about, like a tide, and become the process of reconnecting the inner life of newly individualised humans.

This is the central meaning of Christianity. It is why it was experienced as a liberation. It is its secret life – and is also so potent for our task now: to rediscover a lost soulfulness and vitality.

We can become consciously and wholly orientated towards the divine that is within us. I don’t think that will come about in the ways that modern Christians often expect it will. First, we need to absorb what Barfield and others have discovered about consciousness, its evolution, and its potential. It’s the driving concern of my book.

Does this have anything to do with the Axial Age?

This account of the evolution of consciousness raises a fascinating question. When did it begin to unfold? When did the new consciousness take root? In whom did it find its first flowering?

Barfield realised that there will be eras when, looking back through the prism of words, we can see original participation dominating and, then, eras in which the withdrawal of participation is operative and early experiences of reciprocal participation stand out. Historically, they will look like pivotal periods during which the nature of human consciousness undergoes processes of fundamental change.

It is often called the Axial Age or, as I think is more accurate, times through which “axial shifts” can be observed developing.

This way of putting it was formulated by the German philosopher, Karl Jaspers. Axial shifts occur when people evolve, not in the usual Darwinian sense but culturally, socio-economically, religiously and, fundamentally for Barfield, existentially – in terms of their sense of themselves.

It’s a psychological transformation that can be tracked through the evolution of those fossils of the psyche, words.

Jaspers didn’t do it that way but instead discussed how cultures come to recognise key, transitional individuals. Examples include Socrates, Lao Tzu, Confucius and the Buddha. They had grappled with the inner changes in the experience of being human and tried to make sense of them.

To their contemporaries, they seemed like odd characters with an unhealthily interest in disturbing, blasphemous practices like meditating and questioning. But they were subsequently remembered as iconic because they managed to fashion philosophies of life that could support the ways increasingly required for human flourishing.

During axial shifts, human beings “dared to rely on themselves as individuals”, as Jaspers put it. They confronted traditional ways of doing things. It meant that “hitherto unconsciously accepted ideas, customs and conditions were subjected to examination” so that human beings might be more “open to new and boundless possibilities”.

They did it by connecting with a new sense of inner life.

How might consciousness shift again?

In fact, the withdrawal of participation need not result in an alienated, meaningless, empty dead end. It can lead to what Barfield called “reciprocal participation”.

This is a phase in which the inner life of the individual is felt to reflect, and be reflected in, the rediscovered inner life of the cosmos and, possibly, of God. It’s a kind of return to the earlier experience of original participation, though with a crucial difference.

Life can now be owned by the individual, who can approach it with more conscious, subjectively forged purposes and intentions. To put it another way, a degree of human freedom enters the world.

It’s like noticing the difference between the innate poetry of words and the delight found in a deliberately formed metaphor or verse. The awareness of participating in life is no longer located, primarily, in externally shared rites and music, but internally, in minds. We are not just conscious, as many animals clearly are. We are not just self-conscious, as ancient peoples were. We can nurture our consciousness relatively independently.

We don’t just delight in what’s disclosed but in the power of disclosure, too.

Barfield writes: “[Man] has had to wrestle his subjectivity out of the world of his experience by polarizing that world gradually into a duality. And this is the duality of objective-subjective, or outer-inner, which now seems so fundamental because we have inherited it along with language.”

But if our distant ancestors were not onlookers but immersed participants and myth-makers, the development of language has enabled us to take an inner step back, and that brings new possibilities with it.

What happened next to the human experience of life?

In time, a different sense of life emerged. It came in a new phase of the development of consciousness. To stories and myths was added literature and abstract thought, then the detached meaning of words and, with that, finally, the inwardness of individuality.

It brought the self-awareness that is familiar to us, of a mental space within which essentially private thoughts and experiences autonomously rise and fall.

It’s the dominant sense of being human now. There is what’s me and what’s not me. What’s mortal seems separate from what’s immortal, as does my inner life from the life of the cosmos – to the extent that it’s routinely possible to doubt both the life of the cosmos and of immortal life.

God has died, as Nietzsche observed, and we have killed him.

In this absence, we readily feel ourselves to be specks of encapsulated sentience lost in deserts of mechanistic expanse. Or worse. Neuroscience can make people suspect that they don’t have an inner life at all, as if their thoughts and feelings were nothing but firing neurons and surging hormones.

As the neuroscientist and historian of ideas, Iain McGilchrist, points out, we need constantly reminding that whilst the brain does indeed light up when we eat a cheese sandwich, a brain doesn’t taste cheese. We do.

Barfield called this experience a “withdrawal of participation”. It is the period during which early quasi-scientific ideas about the cosmos were formed. Humans turned somewhat away from old myths, as they started to seek not to share in nature but to explain the constants of nature. For the first time, they had to ask about the meaning of life because its meaning no longer spontaneously revealed itself to them. People could become cut-off, alienated.

But with the withdrawal of participation came an astonishing gain too. The concentration of inner life that separation brought came hand in hand with an intensification of the sense of being an individual. And with that came all manner of novel possibilities.

Moral responsibility emerges, as do new relationships with deities. For example, our ancestors started questioning their fate, as if it were maybe not deemed by the gods, and instead pit their wills against blind fortune and formed complaints against divine injustice.

What was the earlier consciousness like?

If what has been said about the spiritual origins of language is right, along with its intimate connection to the emergence of human consciousness, that mentality must originally have been very different from now.

Barfield called this earlier experience of things, “original participation”. It’s similar to what the French ethnologist, Lucien Lévy-Brühl, called participation mystique, an experience of life in which there is little distinction between what’s inner and what’s outer because the modern boundaries of individual self-consciousness do not yet exist.

The primary mode of experience is collective. There is felt to be a continuous experience of movement between what is me and not me, of blurry lines between mortal and immortal, between past and present, and also between other creatures and the human creature. “Early man did not observe nature in our detached way. He participated mentally and physically in her inner and outer processes,” Barfield writes.

The inner life of the cosmos was the inner life of people. And that was shared. Considering the link between “wind” and “spirit” that Emerson noted is helpful. The old word, pneuma, which can mean both, is an expression of the undifferentiated consciousness of original participation. Back then, the material world mingled with the immaterial; outer with inner; wind with spirit.

It’s an experience of life not wholly alien to us today, and which is enormously attractive when glimpsed.

There’s a powerful sense of it in poetry, of course, and when enacting rituals like lighting candles, and in other activities like harmonious singing, which is a kind of temporary dissolution of the boundaries between oneself and others; or in the waves of emotion that sweep across a crowd; or in the moment when you forget yourself in the heat of the Sun because it warms both body and soul.

Or in the ecstasy induced by psychedelics and entheogens – although that analogue can be misleading if it implies that ancient people were in perpetual states of frenzy or trance, as Julian Jaynes described in, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind.

Rather, early people experienced life from the shared outside in, not the isolated inside out, as we’re inclined to. Their self-consciousness was embedded in their other-consciousness, not their individuality. So when they took psychedelics, I imagine it enhanced what they already knew.

That’s very different from the individuals today who reach for psychedelics to dissolve and smash through their sense of lostness and isolation in a longing to break out.

It’s for this type of reason that the people who experienced original participation have left monuments and artefacts that still greatly impress us. The most obvious are the great pyramids of Giza, built by the ancient Egyptians to reach out to the life of the celestial divinities manifest in the rhythms of the stars, the Sun and the Nile.

It would have taken the resources of the entire nation to construct what became the tallest manmade structures for almost 4,000 years. It’s now known that it was not slavery that kept them hauling the massive limestone blocks up long ramps, rising tens of meters into the air, and setting them in place at a rate of one every two and a half minutes month on month, year on year. The people must have been assured by the activity. They belonged to it.

It was their inner and outer life.

Others, more ancient than the ancient Egyptians, looked not to buildings but to the natural world. They painted aurochs, horses and deer in ochre, whites and blacks on the back walls of dark caves. The images of Paleolithic humans, now preserved in the grottos of the French Dordogne, must have helped develop their conscious association with other animals, their union with the rhythms of the seasons.

Nowadays, the braying heads, shadows, and galloping bodies take our breath away. When Picasso first saw them, he famously remarked that art had learned nothing since.

What has impressed me about them is the sense of belonging to a stream of life that must have been utterly engaging back then. I was struck by how the surviving paintings appear to have served ancient people’s needs for millennia because, once the original pictures were done, no-one from one generation to the next thought of making additions, amendments or improvements. They were maintained and stayed the same.

It must have been the case that what mattered was not innovating, which is indicative of an isolated, agitated mind.

That’s another sign of original participation: people were who they were because they belonged to others. Life was fundamentally social, the communal crucial. Changing the cave images, let alone erasing them, might have felt like a kind of suicide, maybe a genocide. Presumably, it would have been a sacrilege.

It has an uncanny allure for us now, an experience brilliantly caught in a scene from Werner Herzog’s film, Cave Of Forgotten Dreams.

In it, an expert on the rock paintings of Australian Aborigines describes traveling with an Aborigine to a remote site, where he hoped to document some rare specimens of the art. When they arrived, the Aborigine began touching up the images, at which the expert was shocked. He intervened, fearing the loss of valuable data. What are you doing, he asked?!

I’m not doing anything, the Aborigine replied. It is the Spirit, the Aborigine stated and quietly continued.

His was a consciousness still shaped by a participatory mode of being. It was directly in touch with the pulse of life. The difference between the past and present meant little to him. The relationship between himself, his ancestors and the Spirit was similarly continuous. He was informed by values often incommensurate with our own.

Another fascinating account of the collision of original participation with our consciousness can be found in the writing of Daniel L. Everett, a former missionary and linguist. He traveled to the South American rainforest to convert the Pirahã tribespeople to Christianity, and quickly found himself immersed in a world of spirits that the people relate to in arresting ways.

They are fully visible to them, not ghostly or inferred, Everett reports. A tree could simultaneously be a spirit, as could a jaguar. The world seen by the Pirahãs has a spiritual concreteness that is as irrefutable to them as the cash value of the paper called money is to us.

Everett found it disorientating and confusing. Where they saw a spirit, he could not. He saw only an animal or object or, at times, thin air. “I have seen an entire village yelling at a beach on which they claim to see a spirit but where I can see nothing,” he writes. “I have almost lost my life by going out to ‘scare off’ a spirit at their request at 3am, only to realize that the spirit was a jaguar!”

Similarly, to don a ritual mask is not to pretend to be a spirit, or to represent a spirit. It is to become the spirit.

If you don’t write it off as a superstitious, collective hallucination, the implication is that a participative perception of reality has an immediate quality of aliveness that is hard to sustain, or seems simply fantastical, to modern, scientific consciousness.

Aren’t these just “metaphors we live by”?

There is a more instrumental thesis that tries to explain the evolution of words and this shifting of sense. It treats them as soulless signs that gain meaning from human empirical experience, and human empirical experience alone.

It insists that, at root, words are just labels for objects, or to put it a little more specifically, they refer to entities that are detected by our senses.

Jeremy Bentham clearly believed this: “In a word, our ideas coming, all of them, from our senses, from what other source can the signs of them – from what other source can our language – come?” Bentham clearly didn’t consider the spiritual, inside of reality to be a valid source.

A more recent formulation of the approach is found in the influential book by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By. They argue that words initially come from the physical experience of having a body and living in an embodied environment, which is to say, again, that words spring from our senses.

They could cite many possible examples. Take “right” and “wrong” that come from the Latin rectus, referring to a straight muscle, and the Germanic word wrangh meaning sour or tart, respectively. This thesis would say that the inner, and now ordinary, meaning of “right” and “wrong” relate directly to what our senses tell us about certain physical experiences. And there is clearly something in it. If something is right, we are still quite likely to straighten our muscles and sit up as we take notice. If something is wrong, we may well first detect it as we half think, “that just doesn’t smell right”.

Where these theories differ from Barfield’s is in arguing that words do not discover any reality beyond the human, the empirical, the physical.

Lakoff and Johnson, alongside Bentham, conclude that words fabricate immaterial and felt worlds by making inventive but essentially artificial inferences. They would say that our use of words constructs our inner or mental experience of life, but tells us little or nothing about the inner nature of reality, which it’s assumed is basically material, not spiritual.

In that domain, there is no “inner” to be uncovered.

But Barfield belongs to the school that does not simply except that nature is dead because, in truth, words are “a reminder of the time that mind and nature were not thought of as contrary entities,” nature writer, Richard Mabey, avers. He noticed similar links and continues, words are “allusions to how things came to be, and a confirmation of the unity of life.”

There is a correspondence between our inner lives and the inner life of the cosmos. As Barfield put it: “Consciousness is not a tiny bit of the world stuck onto the rest of it. It is the inside of the whole world.”

But his ideas don’t end with poetry, do they?

No. Barfield had noticed something further about the inner meanings of words. It has to do with the evolving relationship between that sense and the outer meaning.

Just to recap: the outer meaning of a word is its literal or surface meaning. It typically refers to something tangible that exists in the external, physical world. The inner meaning is the poetry, the felt or intangible meaning. It typically refers to something that’s real but implicit.

Take, “outsider”. In everyday use, this word means a person who doesn’t belong to the group. That’s its external meaning. But it also carries an inner meaning, the character of an outsider who may be a loner, a misfit, a genius, a rake. The word carries both senses.

What Barfield noticed is that many words in everyday use today, no longer immediately convey both their inner and outer meanings, though they once did, because the external meaning has become less obvious. You might have to do some work to recover it – sometimes not much work, sometimes quite a lot.

Examples in which you don’t have to do much work include, say, “influence”, meaning affect. It’s relatively quickly recognised as “in-flow” or “flowing in”, which links back to its outer meaning, that referred to the inflow of the astrological quintessence of celestial bodies.

“Understanding” similarly meant “standing under”.

Or there are phrases like “letting off steam” or “going off the rails”, which a moment’s reflection reveals as terms that came from the age of the steam engine. Similarly, to refer to a “tension” between people is to use a metaphor that is drawn from the discovery of electrically charged bodies. People can exhibit an electrostatic-like tension between them, causing metaphorical sparks to fly.

But there’s something else you discover if you play the game. It turns out that the exterior meaning of very many, if not most words has now been almost completely eclipsed.

A fun example is “scruple”. Its meaning now, of a doubt or qualm, is actually only its inner meaning. Originally, in Latin, a scrupus was a jagged stone. Cicero added to that by finding the word’s hidden poetry and punning on it alongside another Latin word, scrupulus, which was a tiny unit of measure. He put the two meanings together, which in time morphed scrupus into scruple, a small niggling worry. The inner meaning has come to dominate and now eclipses the original external meaning entirely.

Here are a few more:

The list goes on.

And so on and so on.

Barfield noticed further that the shift from outer to inner meanings alone often produces a narrowing of meaning. “Cupidity”, from the god of love, Cupid, now means greed or avarice, which is just a small part of what the Romans imagined you experienced when Cupid drew back his bow. “Eros”, too, the equivalent Greek deity, was associated with all kinds of passion, not only sexual desire. Homer’s warriors step onto the battlefield full of eros.

All in all, it’s as if people first felt the external world had an inside, too, which was captured in words, though now, we’re inclined to lose touch with it and so, more often than not, feel that interiority belongs to our inner lives alone. The natural world is left seeming relatively mechanical, disenchanted, spiritually dead.

You could say that this is why we now need poets. They can re-expand the meaning of words, as they release their richness afresh, thereby reinvigorating our experience of life. And there’s a clue in that need which suggests that hunting for the meaning of words is not only a parlour game. It might matter greatly.

Barfield put this theory together in another book, arguably his masterpiece: Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry (1957). It’s a multifaceted work, saying a lot about the ancient Hebrews and Greeks, the emergence of Christianity, and also the modern world. These elements are what I pick up in my own book. However, he also addresses the significance of changes in the meaning of words.

It has to do with this overall direction of travel as words change and narrow in meaning. The evolution is from an outer and inner meaning to an inner meaning alone, with the outer meaning tending to become lost.

When Barfield started giving talks in America, after the death of C.S. Lewis, he was occasionally challenged with supposed counterexamples, but further philological investigation revealed more examples of the trend. In common words, it rarely, if ever, happens the other way around.

In fact, he was not the first to note it. In his talks and writings, Barfield often quotes two prominent thinkers who thought about what this feature of words means, too. They are arresting authorities because they are otherwise utterly different in worldview. One is the American transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson; the other, the British utilitarian, Jeremy Bentham.

Emerson put it like this, in his essay, “Nature”.

“Every word which is used to express a moral or intellectual fact, if traced to its root, is found to be borrowed from material appearance. Right means straight; wrong means twisted. Spirit primarily means wind; transgression, the crossing of a line; supercilious, the raising of the eyebrows. We say the heart to express emotion, the head to denote thought, and thought and emotion are words borrowed from sensible things, and now appropriated to spiritual nature. Most of the process by which this transformation is made, is hidden from us in the remote time when language was framed.”

Jeremy Bentham summed it up in this way, in his Essay on Language:

“Throughout the whole field of language, parallel to the line of what may be termed the material language, and expressed by the same words, runs a line of what may be termed the immaterial language. Not that to every word that has a material import there belongs also an immaterial one; but that to every word that has an immaterial import, there belongs, or at least did belong, a material one.”

It’s a remarkable observation. It chimes with Romantic philosophy and Barfield’s sense that words have something crucial to tell us about their soulful nature as well as the spiritual nature of the world in which words are born.

What did the other Inklings make of the idea?

Poetic Diction was warmly received by the Inklings.

It persuaded Lewis that poetry and metaphor are a means, and perhaps the main means, to the discovery of new insights. In fact, the book may lie indirectly behind Lewis’s conversion to Christianity, which came in 1931.

He was then convinced by Tolkien’s argument that the historical life of Jesus was a true myth, a change of mind that requires an awakened sense that behind the literal lies a vitality that is in communion with the heart of reality, which theists call God.

Lewis’s indebtedness to Barfield for his discovery of the divine is implied in the dedication of Lewis’s book, The Allegory of Love. It is to Barfield, “Wisest and Best of My Unofficial Teachers”. Lewis was working on the book during the period leading up to his conversion.

Tolkien gained much from the book as well. The elves in The Lord of the Rings are in many ways a re-imagining of an ancient society in which language is still poetic. Its evolutionary ideas also informed his invention of long forgotten tongues. The Tolkien scholar, Verlyn Flieger, cites a line from The Hobbit that is thoroughly Barfieldian: “Men changed the language that they learned of elves in the days when all the world was wonderful.”

Another occasional Inkling, and future Christian ashram leader, Bede Griffiths, said Poetic Diction “had a permanent effect upon my life.”

Why is poetry so important in his thesis?

Discovering the etymology of words is fun but it doesn’t quite capture the full, revelatory impact of the imagination that Barfield sought. So next he turned to poetry and another book, Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning (1928). It’s had a lasting impact.

His focused shifted. He no longer drew on etymology but on literary theory, with the result that Poetic Diction is not so much a survey of how words are like fossils, as it is an explanation as to how they hold and also can be made to release the past.

He does this by showing how words are not just verbal signs with dictionary meanings. More importantly, they have an inner life. Hence their potency.

Poetry seeks it out, via the inventiveness of analogies and metaphors, and the composition of lines and verses. The task of the poet is to put words together in such an order that their soul is released. Their work enables readers to receive the vitality.

It is experienced as a “felt change of consciousness”, as Barfield put it in a key phrase, the word “felt” having been suggested by Lewis. The good poet not only enables a reader to see the world differently, by expanding on the ambivalences, ambiguities, resonances and complexity of things. There’s another, subtler transmission that occurs as poetic words are uttered.

The reader feels his or her surroundings and inner life light up. It’s as if the metre and the metaphors transform the sounds into sunrays that pick out features of the landscape. A poetic experience is both of something being disclosed and of the thrill of the disclosure itself.

It happens because, crucially, poetry does not play on the surface of things, as if it were a self-generating, self-referential dance, the doctrine that during Barfield’s lifetime came to be called the New Criticism, a precursor to postmodernism. No. Poetry illuminates reality at depth because words participate in reality at depth. They bridge and connect, rather than construct and manufacture.

They are agents of revelation.

Barfield offered an example to help a reader tune into the effect. Consider the difference between how a prose writer might write, “old prophets”, and how a poet would write, “prophets old”. The re-arrangement alters what is conveyed.

“Old prophets” is informative. It refers to prophets who lived many years ago.

“Prophets old”, though, has a very different feel. It is more like an invocation of the old prophets, drawing attention to who they might have been and what they might have known. The reversed word order suggests that it’s possible to share in the spirit of the prophets. A mind might open as it admits the phrase, “prophets old”.

It is this felt dynamic, generated by literary and compositional devices, rhymes and similes, that matters. Barfield likened what they do for words to what is produced by the movement of wire between the poles of a magnet. The action generates something surprising, something new. Electricity flows as the wire traverses the field. There’s a current, a materialisation of energy.

He wrote: “So it is with the poetic mood, which, like the dreams to which it has so often been compared, is kindled by the passage from one place of consciousness to another. It lives during the moment of transition and then dies, and if it is to be repeated, some means must be found of renewing the transition itself.” This is what poetry does.

But the secret liveliness of words, and the sense of awakening poetry brings to awareness, is not all that is achieved. Something further is revealed that has to do with the history of the changing meaning of words. A careful examination of the impact of poetic diction upon consciousness shows that words actually exhibit two types of vitality. One is released by the poet’s skill. Another is inherent in words themselves. Barfield highlighted the second type as the original soul of a word, and in terms of discerning the evolution of human consciousness, it is of fundamental importance.

An example he offers reflects on the changing meaning of the word, “ruin”. Originally, it comes from the Greek verb, reo, meaning “to flow”.

Then, in time, this meaning became the Latin verb, ruo, meaning “to rush” or “fall”. The word that had first evoked movement, perhaps vigorous movement given the rumbling “r”, came also to imply movement in a specific direction, towards collapse. The soul of the word gave birth to the new meaning.

That meaning shifted again when the substantive “ruina”, or ruin, emerged. A further meaning has been crystalized. Now, the word doesn’t just convey the sense of something flowing, or of something falling, but of something fallen. A ruin.

This meaning has become the settled, dictionary meaning, which is where the poet comes in. Through their art and alchemy, they are able to resurface the older meanings that have become embedded in the subconscious of the word, thereby rekindling the full range of its inherent power.

The poet with the greatest power in this respect, if measured by the number of words he revived, is William Shakespeare. His generative capacities were no doubt a result of his gift, though he also lived in a time ripe for semantic rediscoveries. “English meaning had suddenly begun to ferment and bubble furiously round a brain in a Stratford cottage,” Barfield writes. And not least of Shakespeare’s many discoveries concerns the hidden depths of the word “ruin”. He could capture all its meanings and energy in a single sentence, as he does at the climax of his history play, King John. It is a moment of linguistic magic.

The king’s young nephew, Arthur, has thrown himself from the castle walls. The fall kills him, a bloody end to a short life. His body is discovered by the Earl of Salisbury, and Barfield invites us to listen to the words Shakespeare gives to the nobleman as he approaches the crumpled form. The earl describes himself “kneeling before this ruin of sweet life.”

The use of “ruin” in that sentence releases a blast of awareness. “Shakespeare has felt the exact, whole significance of his word,” Barfield explains. “The dead boy has fallen from the walls; the sweet life, which was in him too, has crumbled away; but wait – by Shakespeare’s time the word was beginning to acquire its other meaning of the actual remains – and there is the shattered body lying on the ground! He has, indeed, found a soul in the word.”

Further, at the point in the plot when poor Arthur’s ruined corpse is found, the play itself is nearing the end of its flow, rushing towards its end, which will see the ruin of many. The word captures the exact experience of the audience in that moment too. With Salisbury, we kneel before the ruin of sweet life.

It’s just one example, but it illustrates a general point. The instinctive poetry located in the ancient meaning of words can be reignited. Flow-collapse-ruin. For Barfield, that’s only possible because words spring from a reality that is, at base, not caged and material in nature, but is free and packed with the pulse of life. You could say that words contain a natural poetry.

Barfield quotes the well-known summary of this thesis, now associated with the Romantic movement, found in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “A Defence of Poetry”. “In the infancy of society every author is necessarily a poet, because language itself is poetry… Every original language near to its source is itself the chaos of a cyclic poem.”

To put it another way, primordial thinking was done in the form of myths and memories, invocations and poetry. The poetic art today is one of the ways of recalling the forgotten life of our distance ancestors.

That’s another part of its thrill. Though something novel is added too. Today’s composed poems and chosen metaphors are doubly powerful because they are deliberate. The contemporary writer is aware of what they are trying to do. They are letting the words speak for themselves by consciously causing the words to speak. The reader shares in the creative aspect of the enterprise too, which is why there’s delight not only in what’s disclosed but in the act of disclosure.

All in all, Poetic Diction puts forward a multileveled thesis. It discusses how poetry works. It proposes that words and languages were originally poetic. And it argues that the poetic use of language now delights us not only because it adds colour to life and reminds us of more ancient associations but, in so doing, it raises our consciousness of ourselves.

It invites us to become mindful sharers in the meaning of life, thereby reminding us that life has meaning. It’s why reading poetry, hearing lyrics and watching plays is so therapeutic.

What did he mean that words are “fossils of consciousness”?

History in English Words (1926) was Barfield’s first book length attempt to articulate his ideas about words, and to see how far his intuition about their active nature could really take him.

In the book, he treats them like fossils. Much as the petrified remains of skeletons and shells tell biologists about the evolution of plants and animals, so the old meanings of words, preserved in the bouncing echoes of their historical use, can tell philologists about the evolution of the human minds that deployed them.

At one level, History in English Words is, therefore, an etymological compendium. It retells the stories of hundreds of words that were heard as the British islands were invaded from abroad and as its people’s embraced cultural changes. It makes for a fascinating read, particularly if you love trivia.

But at another level, the book is a theory of knowledge and a history of the mind. “Words may be made to disgorge the past,” Barfield explains, to show the twists and turns of the evolution of our consciousness. Like fossils buried in the strata of rock, they reveal “a change not only in the ideas people have formed about the world, but a change in the very world they experience.”

It is a bold thesis, a big idea. W.H Auden wrote an enthusiastic forward, arguing it “must be made required reading in all schools.”

So Barfield began to think that words have soul?

Barfield began to work out why his newfound spiritual perception was not fanciful and located the reason in language.

Words have meaning, he said, stating the obvious. No-one can deny that. And they have meaning because they are not like the algebraic signs of abstract logic: x, y, α, β. Rather, they share in what they describe via metaphor. They channel.

Even scientific words make direct links to the richness of reality, and draw on that vitality. If they didn’t, scientific theories would become uncoupled from the world and self-empty of meaning. Barfield was on the side of those who resist the kind of science that becomes “life-blind”, as the philosopher of science, Mary Midgley, calls it.

Think of a few scientific words. “Force”, “machine”, “energy”, “gravity”, “work”, “law”, “evolution”, “adaptation”, “fitness”.

They’re all metaphors at root, which becomes clear when they are used in other contexts. “The force of his will.” “The machinations of the princess.” “She has gravitas.” “It’s fit for the gods.”

Just because they are used as scientific terms, doesn’t mean that “force”, “machine”, “gravity”, “fitness” suddenly become colourless ciphers. They retain the potency that is instrumental in detecting the phenomena they describe.

For example, some objected to Newton’s revolutionary theory of forces and gravity when it first appeared because they didn’t like the assertion that there are such things as forces and gravity in nature. Newton’s great rival, Leibnitz, thought that gravity makes sense when referring to human qualities – “She has gravitas” – but becomes pure superstition when used to describe an occult attraction between celestial bodies separated from one another over great distance.

But Newton’s new use of the word “gravity” stuck and it did so because the word has real meaning in its new context. It connects with one aspect of the liveliness of the world, in this case a quality of attraction, and communicates that quality to us. So, too, with other words. Further, it must also be the case that the minds that use such words participate in the liveliness too, directly or indirectly.

This is the secret life of words. They can turn a vague feeling into a clear thought. They are as much like a conjuror’s spell as a logician’s label. They are full of “bottled sunshine,” Barfield said. They have soul. He was to spend the rest of his life unpacking the implications of this point for humanity, the meaning of religion, and the significance of consciousness.

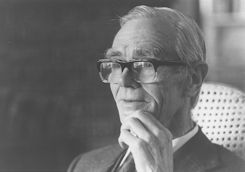

Who was the last Inkling, Owen Barfield?

Owen Barfield was born in 1898, twenty days before C.S. Lewis, during the last years of the Victorian era. He died in 1997, a few months after Tony Blair became British Prime Minister.

Educated at Oxford, a solicitor for most of his working life, he lived in London and Sussex. He wrote novellas, poems, plays, books and essays. In his youth, he became an expert gymnast and philologist.

Above all, he devoted his efforts insofar as he could “to the secret life of words”, as biographers Philip and Carol Zaleski put it in their account of the Inklings. Barfield was a founding member of the fabled circle that included C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. He was the last of them to die.

He first met Lewis when he went up to Wadham College in 1919. It was not a happy time for him. He became acutely depressed by what he later called “the caged materialism of the age”. In a letter to a friend, he described feeling as if he were falling in on himself “like an ingrowing toe-nail”.

“My self is the only thing that exists, and I wear the external world about me like a suit of clothes – my own body included,” he continued. The sense of feeling trapped in his inner life, like a castaway on an island of consciousness, was for a time intolerable.

A combination of love and poetry was his salvation. They brought a redemption that came without warning one evening in 1920 when the clouds of his despondency lifted. It was a radical re-orientating of his mind, a conversion, which he understood as a spiritual awakening: at base, he had been cured of a spiritual disease.

He realised that a desire for beauty, which had been stirred by falling in love with the woman who would become his wife, could be found not only in his mind, not only in his beloved, but throughout the cosmos and nature. There is a store of treasures that is permanent and never ceases giving. The revelation was profound and determinative, shaping the rest of his life.

What’s in a word

A short history of our minds charted in words.

Barfield’s History in English Words is a joy of allusions as well as etymological connections. And there are many very old words he tracks that are still in everyday use.

Did you know that we should thank our distant Aryan ancestors for many names of trees and birds, like “beech” and “hazel”, “finch” and “starling”? Other Aryan words that convey a feel of those times include “garden”, “geese”, “oxen”, “sows”, “hounds”, “milk”, “weave”, “axle”, “wheel”, “yoke”, “fire”, “night”, “star”, “thunder”, “wind”.

What I’ve done here is pick one word for each century over the last 2,500 years, beginning with the Athenian Greeks and the word, “philosophy”.

5th century BCE – “philosophy”

It must have felt very Pythagorean when first used by Plato, with its roots reaching back into the 6th century BCE, and possibly Egyptian origins. It would have carried echoes of sacred astronomy, geometry and number, and comes in with other words like “cosmos”, “chord”, “harmony”, “metaphor”, “rhetoric”.

4th century BCE – “quality”

This word is Cicero’s translation of Plato’s neologism, “poiotes” or “whatness”, remembering one of Plato’s key gifts: to think about the feel, worth and intrinsic fit of things. It’s linked to another central dynamic for Plato, namely love. He meant it as that which enables us to rise from the contemplation of the transient aspect to the eternal aspect, from the visible to the invisible, from the mortal to the immortal, and thereby discover new dimensions within ourselves.

It’s also worth noting that Plato didn’t have words we now naturally associate with philosophy, like “quantity” or “metaphysics”. They were created by his great pupil, Aristotle.

3rd century BCE – “fantasy”

“Fantasy” and “fancy”, in the Greek, became popular with the emergence of the Stoics. They had a somewhat sceptical attitude towards the old religions, regarding their own sense of Zeus as an improvement. “Image” was an Epicurean idea, as the thin film or husk thrown off from surfaces that enter the eye when seen or detected. The Stoics also coined “etymology”, the true meaning of words, which says much about their interests, as well.

2nd century BCE – “logos”

This rich word for “word”, that also resounds with “argument”, “law”, “reason” and “tendency”, was contemplated by the pre-Socratic philosopher, Heraclitus, who saw it expressing a key principle of the cosmos. It became the central divine perception for the Stoics and, in this century, one of their number, Diogenes of Babylon, made a celebrated trip to Rome, and the word began to take off more widely.

1st century BCE – “humanity”

This is another one made familiar by Cicero’s genius. He combined Greek notions of loving what makes us human and education to create “humanitas”. It was originally about what makes a good speaker: someone who can project a good character, as in “having humanity”.

1st century CE – “martyr”

It means “witness unto death”, an early appearance with this meaning being found in the Biblical book of Acts, where it refers to Stephen, the first martyr. Barfield notes that it’s a rare word still in use that sheds light on novel feelings and experiences from the period. An individual might now know their god so personally that they are prepared to die witnessing to that inner spirit.

2nd century CE – “free will”

All sorts of words to do with the individual start to be born, in fact, pointing to the key legacy of Christianity. For example, someone is accused of “plagiarism” for the first time about now. And it’s Justin Martyr who starts to argue that human individuals have free will, with more or less the same sense that we have.

3rd century CE – “sacrament”

This is a Latin translation of the Greek for “mystery”, used by the Christians to pin down what did and didn’t count as a divine channel. There was probably a democratic impulse at play here, as Christianity became hugely popular with everyday folk in this century. But it had a negative effect on “mystery”. It had referred to an initiation ceremony that yielded a sense of eternal life, but now it’s meaning started to become vaguer.

4th century CE – “confession”

Augustine wrote his brilliant autobiography with this title, more or less inventing the genre. With his Confessions, he opened the flood gate to introspective culture, he himself using far more words to describe his interiority and reflection than are found in older documents like the Bible.

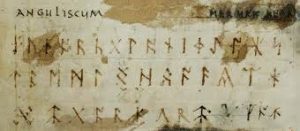

5th century CE – “runes”

This is the traditional date for Anglo-Saxons in Britain, and Old English begins, with runes introduced. They’re important as England, at least, starts to develop an identity of its own, following the withdrawal of the Romans.

6th century CE – “consolation”

Boethius, facing death from a prison in northern Italy, writes his philosophical meditation, The Consolation of Philosophy. It’s a popular work, including beautiful poems, and offers a practical wisdom that restores Platonic philosophy. Dante’s vision of the soul finding its true place in the cosmos is an extended elaboration. Chaucer’s philosophical reflections are inconceivable without it.

7th century CE – “Chatrang”

This is an old Persian version of the game of chess. The Arabs discovered it in this century, when they began their conquests following the death of the prophet, Mohammad. The earliest attested English poetry has its origins now, with Beowulf being composed soon after.

8th century CE – “horseshoe”

Horseshoes, heavy ploughs, and horse collars come into use. They mark a revolution in agriculture and so help to sustain larger populations.

9th century CE – “algebra”

From the works of the Persian scholar, al-Kharizmi, “algebra” is an early incorporation from Arabic into English, and with it must have come the sense that serious learning was taking place elsewhere. It’s possible that scientific abstraction starts to be felt about this time, with the spread of Islamic learning. Other Arab words include “cotton”, “gazelle”, “hazard”, “masquerade”, “syrup”, and “tambourine”.

10th century CE – “she”

The Northman, whose presence is felt by the Anglo-Saxons during this century, bring with them their pronouns: “they”, “them”, “their”, and “she”. They also introduce a grammatical achievement, which means that English people can now signify the genitive and the plural by the straightforward addition of the letter “s”.

11th century CE – “Normans”

The Normans arrive in England, the word marking the dynasty having been formed in the previous century, and the conquest initiated an influx of French words, though they weren’t always quickly adopted. For example, it’s said that the English habit of calling an animal by one word when alive, and another when ready to be eaten, reflects a mix of Saxon and French terms. “Oxen, “sheep”, “calves”, “swine” are Saxon. “Beef”, “mutton”, “veal”, “pork”, “bacon” are Norman.

12th century CE – “inquisition”

This comes from Latin for inquiry, and begins to take on its grimmer meaning. That said, it’s a prerequisite for individuality as we know it because only an individual, with private beliefs, might require a visit from the inquisition.

13th century CE – “lovingkindness”

The language of devotion marks this century. The moment can be summed up in the Middle English, “love-longing” – the longing of the Christian for Christ, also meaning a sigh or moan. Other words Barfield notes that spring into life include “pity”, “gentle”, “anguish”, “charity”, “delicate”, “delight”, “grace”, “patience”, “tender”. Courtly love follows, and men begin to feel for women in a way that may not have been possible before.

14th century CE – “conscience”

From the Latin “conscientia”, it originally meant more like “consciousness of” or “knowledge of”; you could have conscience but not possess it for yourself, much like you have happiness but not have “a happiness”. However, it now starts to mean “a conscience”, “my conscience”, and eventually Shakespeare will call it the deity in the human breast.

15th century CE – “accident”

This is a relatively quiet century, words-wise, perhaps due to the turmoil of the Hundred Years’ War. However, one interesting shift is with this word – originally from the Latin for an event; then in Scholastic theology meaning that which is not essential; but now starting to mean a chance, perhaps meaningless, occurrence.

16th century CE – the prefix “self-”

This is a century of semantic revolution on many fronts. The habit begins of coining new Greek-English words to mark a scientific advance, like “automatic”. Francis Bacon gives us the modern senses of all kinds of words – “action” and “business”, “charge” and “accusation”, “idea” and “eloquence”.

But if there’s one change that is more far-reaching than any other for our consciousness, it’s the Reformation tendency to use the prefix “self-”. As believers become preoccupied with their inner life, they start talking about “self-conceit”, “self-liking”, “self-love”, “self-confidence”, “self-command”, “self-contempt”, “self-esteem”, “self-knowledge”, “self-pity”.

17th century CE – “fanatic”

The Puritans try to change the English language by expelling “foreign” words, wanting “hundredr” for “centurion”; “crossed” for “crucified”; “freshman” for “proselyte”. And the Civil War creates its own lasting vocabulary: “puritan”, “malignant”, “independence”, “fanatic”.

Incidentally, lots of financial words emerge, as well: “capital”, “commercial”, “discount”, “insurance”, “investment”…

18th century CE – “speculation”

This word reaches back all the way to Plato, though it meant seeing. Now, Horace Walpole shifts its sense, to become speculation as to take a punt by buying and selling.

19th century CE – “revolutionise”

The root word is older, but now the verb form starts to mean changing something completely and fundamentally. Lots of common scientific words appear, as well: “anaesthetic”, “railroad”, “telephone”, “turbine”; plus mechanical metaphors like “blow off”, “get up steam”, “go off the rails”, “tension”, “charged”.

20th century CE – “gadget”

Here’s just one word with an striking etymology. It comes from the First World War, the war in which machines were first deployed to destroy human life on the large scale, and means a small mechanical contrivance.

Another note that Barfield makes of this century, the one in which he died, is that “improper” was first used of humans in the 1950s.